Garden Blog - September 2025

In 1751, William Hogarth, famed English painter, engraver, cartoonist, and writer, created the well-known satirical print, Gin Lane, as part of a campaign to combat the ‘Gin Craze’, a period of rampant, cheap gin consumption, that fuelled all sorts of social ills. Gin Lane illustrates the problems of its time with scenes of death, starvation, and violence; including a famously drunken, syphilitic mother, dropping her baby into an abyss.

As a result of Hogarth and others railing against the dangers of ‘mother’s ruin’, the Gin Act was implemented, introducing high taxes and strict regulations on gin sales, which did the job of curtailing its uncontrolled consumption.

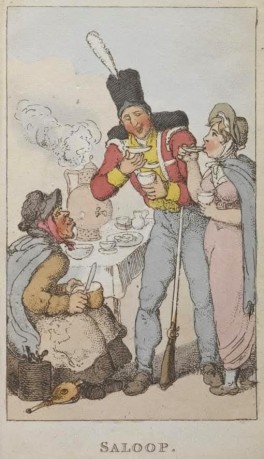

Sobered up poor folks, unable to drink expensive gin, or tea or coffee for that matter, would choose saloop as a cheap alternative, produced from the roots of cuckoo-pint, a native wild flower. The roots of cuckoo-pint, known to botanically minded types as Arum maculatum, are edible if washed and roasted properly.

|

Cuckoo-pint |

Saloop |

When ground, it was, in times gone by, traded under the name of Portland sago, which was then used to make a hot drink called saloop, that was popular with working class folks during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as a cheap alternative to tea and coffee. Served with milk and sugar, saloop was said to be jolly refreshing, unless prepared incorrectly, at which point it was highly toxic and likely to kill you.

What does any of this have to do with September in the garden, you might ask. Well, at this time of year, the distinctive, bright red fruits of cuckoo-pint, sparkle like clusters of rubies in shaded parts of our borders, heralding as they do, along with a host of other plants, the change from summer to autumn. One of those is Cyclamen hederifolium, the common name of which is sowbread, as their corms were thought to look like small loaves and often fed to pigs. Though native to the Mediterranean region, sowbread has been cultivated in British gardens for many centuries, with its first botanical listing here was in John Gerard's famed 1597 work titled, Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes. Forming great carpets of delicate pink and white flowers in areas of dappled shade, they are an arresting sight indeed.

|

Sowbread |

Meanwhile, luxuriating in full sun, our pot-grown Cannas and dahlias are still going strong, and will be smothered in masses of flowers until cut down by the first frosts. At that point they will have their foliage cut off, be removed from their pots, divided, re-potted, and kept frost free in our polytunnel to overwinter. Other tender perennials, such as pelargoniums, salvias, plectranthus, et al, are grown as new plants produced by cuttings taken at this time of year.

|

Potted Dahlias |

Most tender perennial cuttings are nodal, meaning that the cut is made just below a leaf joint, otherwise known as a node, where there is a concentration of hormones to stimulate root production.

-

For best results, collect non-flowering shoots, as they will root more readily.

-

Using a sharp knife or secateurs, trim below a leaf joint to make a cutting that is roughly 5-10cm in length, remove lower leaves, and dip the cutting base in hormone rooting powder or liquid.

-

Fill a small pot with seed and cutting compost and insert several cuttings around the edge of the pot.

-

Label the pot, and water it gently from above.

-

Place the pot in a closed propagator with bottom heat of 18-24c, or cover with a transparent plastic bag, and place somewhere warm and light.

-

Remove the propagator lid or plastic bag for a short while a couple of times each week for proper ventilation, and to reduce the risk of fungal disease.

-

Ensure the compost remains moist until the cutting are rooted, which will take between two and four weeks.

-

Regularly remove any dead, dying, rotting, or diseased material.

-

Once successfully rooted, the new plants can be separated and potted up into a good multipurpose compost.

On that productive note, until next month, happy gardening.